What they are they

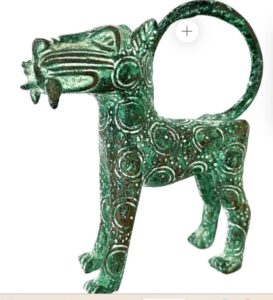

Artistically and beautifully created by expert craftsmen from Benin City in what’s now southwest Nigeria, the Benin Bronzes are a group of plaques and sculptures that adorned the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin. These artifacts were created by the Edo (Benin) people from at least the 13th century onwards, reaching their artistic peak in the 16th and 17th centuries. The bronzes include intricately detailed plaques, statues, and various ceremonial objects, showcasing the sophisticated craftsmanship of the Benin artisans.

In addition to bronze regalia, plaques and sculptures of people and animals, the haul included ivory, coral and wooden items.

What went wrong

The Benin Kingdom was among the best organised and wealthiest, not only culturally but economically in Africa. Britain’s attempt to expand its political and commercial reach in West Africa by taking it over was met by resistance of the Oba (King) of Benin. A “peace” delegation was sent from London to discuss sending the king into exile to halt his trade monopoly around the Niger Delta and colonising his kingdom. The delegation was ambushed by the natives. British forces were sent on the notorious Punitive Expedition. A massive destruction of lives and properties ensued.

The invaders looted what has become known as the Benin Bronzes.

Faith of the bronzes

On arrival in England, some were given to Queen Victoria on some other members of the royal family. To offset the costs of the expedition, the bulk of the loot were sold to various museums, private collectors, universities, and institutions, local, regional, national and international around the world – including religious bodies, notably the Church of England.

The Benin Bronzes are the most traded artifacts from a single source in the history of mankind. Every single one of the over 5000 of them tells a story – of love, of life, of divinity, of war, of peace. Stories that mean so much to the the Benin people, socially, culturally and spiritually. And, stories that have never ceased to amaze those who unethically keep the heart and soul of an African people.

The takers of stolen goods

Too many to name. But here are a few of them.

- United Kingdom:

- British Museum, London: One of the largest collections of Benin Bronzes, with hundreds of pieces.

- Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford.

- Germany:

- Ethnological Museum, Berlin: Houses a significant number of Benin Bronzes.

- Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum, Cologne.

- United States:

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- France:

- Quai Branly Museum, Paris.

- Other Countries:

- National Museum of Ireland, Dublin.

- World Museum, Vienna, Austria.

And in the Netherlands too...

Information from a report into the Benin Bronzes published in 2021 by the Wereldmuseum claimed that 4 Dutch museums have 114 Benin Bronzes artifacts in their collections. They are found in (1) the Museum Volkenkunde in Leiden, (2) the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, (3) the Afrika Museum in Berg en Dal and (4) Wereldmuseum in Rotterdam,

In the little house that showcases West African (Nigerian) artifacts in the Kura Hulanda Museum, Kòrsou, a couple of replica of the Benin Bronzes are on display.

What the future holds

Nigeria has been seeking the return of the looted artifacts for much of the 20th century without success. The call grew louder after independence from Britain in 1960. Some Western curators felt that antiquities such as the Benin Bronzes should be considered part of a shared, global heritage rather than the property of a single nation. They believed the job of protecting, displaying and loaning them should go to those best placed to handle this responsibility.

Not surprisingly,the British Museum, which keeps more than 900 of the artifacts, is legally prevented from returning them under the British Museum (1963) and Heritage (1983) acts.

Who is returning what

The UK is almost alone in its opposition to returning the looted artifacts. It should be mentioned that despite its self-imposed legislation against it, the British Museum sold more than 30 of the artifacts to the Nigerian government between 1950 and 1972. As for those who received the stolen goods, most of the Nordic countries are taking steps to ensure the return of the items to Nigeria. In April 2021, the German government declared that all the over 1.100 looted Benin bronzes in Germany’s public collections must be returned by 2022 unconditionally. In November 2021, the Quai Branly Museum in Paris returned 26 of the artifacts that they hold. In the USA, the Smithsonian Institution announced plans in 2021 to return most of its Benin Bronzes to Nigeria. They are in the process of doing so. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York also pledged to do the same

The Dutch government declared that the items that were “wrongfully brought to the Netherlands” must be returned to their rightful sources.

In the UK, other than the stock held by the government in the public domain such as in the British Museum and with the royal family, various institutions agreed that it is morally and ethically wrong to keep good obtained under such circumstances. Those that decided to return them include the Jesus College of Cambridge University, Oxford University, University of Aberdeen, the Horniman Museum in London, the Great North Museum, Newcastle, and some private collectors, including the Church of England which is taking positive steps along this line.

The surge in the drive for restitution since 2021 (following the Gorge Floyd episode) are part of a broader recognition of the need to address the historical injustices, including those associated with the colonial looting of cultural heritage.

.

Dissent from the diaspora

In 2022, an African-American slavery reparations activist group in the US, an organisation concerned with slavery justice, called the Restitution Study Group, petitioned the UK’s Charity Commission against repatriating the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria. The group argued that present-day southwest Nigerians should not benefit from the bronzes since, as a society, they are descendants of slave traders. Instead, the group proposed that descendants of enslaved Africans should have co-ownership over the Benin Bronzes in Western museums. Also, they would have easier access to the artifacts in the Western nations than in Nigeria.